With Hothouse Bloom, Austyn Wohlers has written a meditation on creativity, connection, and nature. In beautiful prose that creates a dreamy atmosphere — early reviews have likened her to Rachel Cusk and Han Kang —this debut novel offers a modern-day twist on the pastoral.

Her protagonist, Anna, gives up her life in a city and her career as a painter to move to the country and take over an apple orchard she has inherited from her grandfather. She sees this new opportunity as a way out of an existence that she no longer understands, but Anna doesn’t simply change locations and career paths; she decides to completely reimagine her life, giving up her art, her relationships, and even spoken language. In the opening pages we learn, “She had always felt the rituals of life did not make sense. She was afraid of making wrong decisions and therefore afraid of life itself.”

One of her first actions when she arrives at the farm is to remove the sign that names it: “For her the orchard would be nameless, general, platonic, perfect.”

Before long, though, Anna’s plan for an isolated, silent existence is foiled by her friend Jan, an itinerant writer who asks to stay with her for a couple of months. His arrival challenges Anna’s commitment to her new way of being, and the tension between solitude and friendship, nature and society, and the various modes of creativity propel the novel forward as Anna tries to find her way. Jan tries in vain to draw Anna out of herself and Anna, in turn, tries to indoctrinate Jan to her way of living on the farm. Then, as the harvest approaches, the outside world encroaches in the form of pickers, contractors, neighbors, and pomologists. Anna realizes that the only way back to her idyllic life may be to turn a profit.

The novel is moody and atmospheric, and at times it feels akin to the psychedelic pop Wohlers plays in her band, Tomato Flower. There are scenes at once strange and frightening and comical. Anna’s inner monologues are dramatic, touched with subtle humor. As she realizes that she must make money to keep the farm going, her desperation builds into a kind of mania.

Wohlers, a musician as well as a writer, grew up in Atlanta and moved to Baltimore after graduating from Emory College. She founded Tomato Flower in 2021. These days, she finds herself in Baltimore at least once a month, and will return on September 9 for a book launch at Normals Bookstore.

Baltimore Fishbowl: How did the idea for Hothouse Bloom take shape? What was the process of writing it like?

Austyn Wohlers: I was interested in working with the kind of narrator who has difficulty living in the world and seeks solitude, and began with a short story that focused on the orchard and Anna’s relationship with Jan. I wanted to continue to explore that world, so I turned it into a novel.

BFB: Your book explores themes of creativity – both artistic creation and the creation that takes place in nature. Anna, the protagonist, initially rejects the former and commits herself to cultivating the latter. What do you see as the relationship between artistic creation and natural creation? Do you believe, as Anna seems to, that the two are mutually exclusive?

AW: I don’t think they’re mutually exclusive—I think Anna’s dilemma is more about connection versus escape. Like all artistic people, she has some need to externalize the internal, whether through painting or through her perception of life at the orchard. I am pretty outdoorsy and like to hike and swim all summer, and I have always made art relating in some way to the natural world.

My grandmother owns a small berry farm, and my mom had a big flower garden in our yard when I was growing up. That said, I’m very much a city person. I’m interested in psychedelic music and literature and have seen some describe the psychedelic aesthetic as resurfacing distortions of childhood memories, which tracks, I think, for the kind of unreal natural imagery I am drawn to.

BFB: The novel also explores themes of solitude versus human connection. In my experience, this is always a delicate balance, especially for artists. What led you to explore this theme in your book? Do you identify more with Anna, who eschews society altogether, or with Jan who tries to pull her out of her isolation?

AW: I used to feel I had a lot of trouble connecting with people, even though I think I have a lot of friends. I like people a lot and am interested in the differences in how everyone experiences the world. I don’t really feel this way anymore—I think I was just struggling with the kind of psychic aloneness everyone feels for a long time. I’m very social—more like Jan, though maybe I was more like Anna when I was writing the book. I actually think I started engaging in literature out of a desire not to be alone, thinking of narrative as a kind of imaginary social activity.

BFB: Over the course of her time living at the orchard, Anna becomes focused on the financial side of the endeavor. What is the significance of this shift in her attitude?

AW: The book is a critique of a kind of pastoral escapism, which, like most flights from the realities of this world, is fundamentally built on the suffering and exploitation of others.

BFB: Does your work as a musician inform your work as a writer? If so, in what ways?

AW: I am one of those people who needs to be constantly working on something to be happy, so having two outlets is mostly beneficial in that when I get burned out in one sphere I can switch to the other. Music fills a social need and literature a need for solitude. I definitely explore similar themes in both forms.

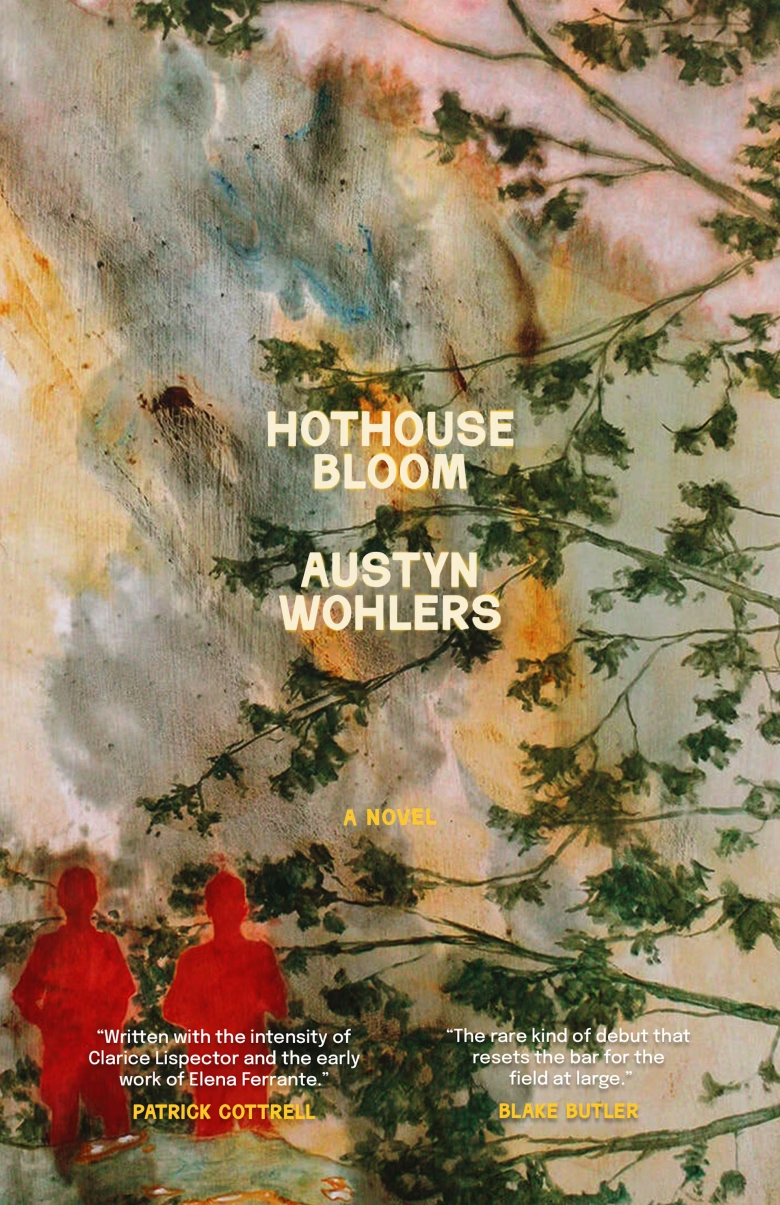

BFB: The cover image is so beautiful. Tell us more about it.

AW: As we were looking for cover art, I was emphatic that I didn’t want it to just look like a run-of-the-mill American nature novel, and that I wanted it to feel a little psychedelic, since so much of the language of the book is watercolory, dizzying, and elemental. I’m happy to have found Daniel Ablitt’s painting, which unites a lot of those elements. The blurriness of landscape and setting—in the background forested mountains, a tree, or a colored ray of light. The focus on flora, which takes up all of Anna’s vision. The two red silhouettes, which could stand for a number of people in the novel but most likely Jan and Anna, which are both stark and a little vague, a little mysterious, and red like the apples Anna cultivates.

BFB: Did you study writing in school? Where?

AW: I studied undergraduate creative writing at Emory, where Jim Grimsley and Jose Quiroga were important mentors to me, and got an MFA at the University of Notre Dame.

BFB: Are there any specific writers or novels that were touchstones for you in writing Hothouse Bloom?

AW: Clarice Lispector, Thoreau, Henri Bosco’s Malicroix, Graciliano Ramos’s Sao Bernardo all come to mind.

BFB: Tell us more about Tomato Flower. At what venues might we see the band? Do you have a favorite club in Baltimore?

AW: I love playing at Mercury Theater in Baltimore; that would probably be my favorite venue. You might see us more regularly at The Compound, Metro Gallery, and Current Space, which are also all quite nice. We are an art rock band with a pop sensibility I would say. We toured with Baltimore legends Animal Collective and, more recently, with the Japanese noise-rock band Melt-Banana. We are currently recording our second album.

Book Launch

Tuesday, September 9, 7 pm

Reading and conversation with Blake Butler

Normals Bookstore, 425 E. 31st St.