Baltimore’s bike share system is close to shutting down once again due to a lack of maintenance from its operator and its equipment’s inability to handle wear. Most troubling, two out of every five bikes in the system have disappeared.

Bewegen, the company contracted to design and install Baltimore Bike Share, had promised a system with 500 bikes—40 percent of them electric-assisted—and 50 stations when the system first rolled out in October 2016. All 500 bikes were delivered to Baltimore.

But on July 14, I rode around to 21 of the 39 operational stations and found only 6 bikes could be successfully checked out, along with another 25 nonfunctional bikes. During my visit to the maintenance facility two days later, I only discovered an additional 250 bikes waiting for service. That means 200 bikes are presently missing from the system.

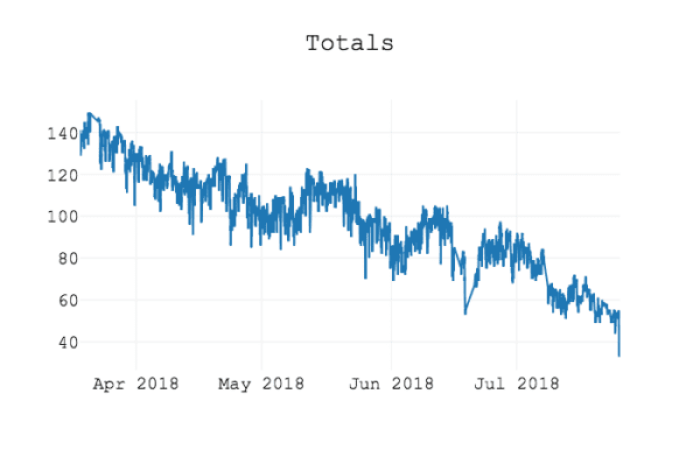

In March, I wrote a script to track the number of bikes in the system every 10 minutes based on the numbers reported by each dock. Rather than explosive growth in bike inventory and usage in Baltimore Bike Share’s second year, the data instead show a system in a downward spiral.

The Baltimore Bike Share app also appears to be losing accuracy. Through mid-May, the number of bikes shown at each dock was very reliable when compared with what was observed in person. But things have deteriorated to the point where the 21 stations I visited reported 27 bikes through the app, while only 6 were operational.

This also happened last summer. Over Labor Day 2017, I rode around to each station and found there were only four operational bikes in total, despite the app reporting 45 available bikes.

Bewegen, which declined to comment for this story, last summer blamed the rapid decline in bike inventory on theft and vandalism.

“We don’t have this issue anywhere else, not at this level,” Bewegen CEO Alan Ayotte said after the first system-wide shutdown in September 2017. “Our locking system is recognized [as] very, very up to industry standard, but due to the issues that occurred in Baltimore this summer, we did add additional security.”

In a statement emailed Wednesday, DOT spokesman German Vigil acknowledged “continued theft and vandalism of bikeshare bikes” as ongoing problems. Citing figures from Bewegen, he said the average repair time for a bike from June 2017 through this past May was almost three hours.

“We are working to deploy additional resources in order to decrease repair time and increase the number of available bikes on the street,” he said.

He added: “We are in the process of assessing and reevaluating the vendor’s ability to stock our bicycle fleet.”

Subpar Equipment

A stark difference is apparent between the Bewegen stations and the stations used in bike share systems in most other major American cities.

Chicago, New York City, Portland, Charlotte, Detroit, Philadelphia, Washington D.C. and other cities with successful bike share systems have docks that are braced at the top, and a locking mechanism on the frame, while Bewegen’s docks utilize two separated pieces of metal, and a locking mechanism on the wheel, leaving them vulnerable to vandalism.

On June 26, local resident J. Christian Parent, tweeted a photo of a damaged dock that he said was bent by an individual repeatedly kicking it until it released the bike. Similar techniques were used in summer 2017, when an individual was caught on video “viciously rocking” a bike to bend the dock, Baltimore police told The Sun.

When I surveyed the bikeshare system on July 14, I found many docks were loose enough that bikes would wobble when docked, and some had significant enough damage that the bikes would not even lock in. A driver–who asked their name not be used in order to speak candidly–employed by Corps Logistics, the company responsible for maintaining and rebalancing the bikes, said bent docks can leave the bikes unable to charge or dock properly.

It appears Corps Logistics, which declined to comment as a company for this story, has also failed to keep stations operational. Many docks rely on battery power when hardwired power is unavailable, requiring batteries to be replaced every few days for bikes to charge and kiosks to operate, according to another Corps Logistics driver who also asked to remain anonymous.

But none of the stations I inspected on July 14 appeared to have functional kiosks, which indicates these batteries are no longer being replaced regularly. One dock at Maryland Avenue and W. Biddle Street was not even functional because it was not registered in the app, meaning a lone docked bike could not be checked out.

Bewegen has also pinned the blame for the lack of bikes on a lack of mechanics. (The company recently posted three openings.) However, when I visited the Corps Logistics bike maintenance yard in Westport on July 16, broken bikes sat lined up or piled in the bushes. Only one of three mechanics present that day was actively working on a bike during my trip.

One of the Corps Logistic drivers said in early June that the two companies are no longer ordering replacement parts at the same rate they used to, especially for electric bikes, due to high costs. Corps Logistics is responsible for the cost of replacement parts.

Liz Cornish, executive director of local cycling advocacy nonprofit Bikemore, is not surprised.

“I took a tour of Corps Logistics’ facility before their launch in 2016. You could see that they did not have the experience, tools or processes to make sure they were putting out safe bikes,” she said. “They didn’t have maintenance techs that would be able to work on bikes with this level of usage, much less the experience of working on ped-electric bikes.”

Ayotte in September 2017 said Bewegen has encountered more “different challenges [in Baltimore] than other places,” while adding, “but the city is 100 percent behind the bike share system, so we’ll make sure we’ll overcome these issues.”

Those challenges include not being able to acquire the parts to roll out all 50 stations on time, and being unable to keep up with required bike maintenance.

Kathy Dominick, a spokeswoman for the Baltimore City Department of Transportation, said that from October 2017 through April of this year, all bikes needed to return to Corps Logistics’ maintenance facility in Westport an average of once per month. DOT declined to share updated data beyond April.

Since the system’s launch, it has been common to find bikes with loose brakes, bent wheels, stuck gear shifters, loose or missing baskets, seats that slip down while riding and misaligned handlebars.

Bikes also lose network connectivity frequently, leaving them unavailable for checkout via the Baltimore Bike Share app. Disconnected bikes require a maintenance driver to do a manual reboot, and the same drivers are responsible for collecting broken bikes and re-deploying fixed bikes, which can mean added delays for rebooting ones that simply lose connectivity.

Federal Hill resident John Bremerman, a member of Baltimore Bike Share since October 2016, said he thinks “faulty equipment and lack of availability [are] holding back the system.” He recalled riding an electric-assisted bike with two hours of charge that died on him in the middle of a short trip.

“Luckily, I was able to return the bike to a docking station with ease, but it did cause me to cut my trip a little bit short.”

Bikes also can become un-rentable if the dock becomes misaligned. One of the Corps Logistics drivers demonstrated there are two points of contact in the dock that must touch to properly dock and charge a bike. The company’s drivers must use a special tool to bend a broken dock back into place.

A dead bike battery will also render a Baltimore Bike Share member’s key fob, used to access bikes at the dock, unusable. In the app, those bikes typically show up as “in maintenance,” “not connected” or “in transit.” The driver who I spoke with said they spend significant time re-aligning docks.

Paul Meyer, a Baltimore Bike Share user since November 2016, said he is unable to check out almost half of the bikes he comes across, even with a key fob, and complains that the bikes are much heavier than those with other bike shares he has used.

And with the ones that he is able to check out? “More often than not the seat is broken.”

@BmoreBikeShare pic.twitter.com/nSr4lGXg0a

— Brian Seel (@cylussec) July 14, 2018

Needed: A Quality Provider

City Councilman Ryan Dorsey wrote in an email that he thinks the city “should be holding the vendor accountable for a breach of contract as they are failing to provide the city what was agreed to.”

One option would be for Baltimore to cut ties with Bewegen and look toward something different.

Jed Weeks, Bikemore’s policy director, noted that DOT is hiring a new bike coordinator who will be responsible for our bike system. “Do we want their first six months to deal with a failing system, or to deal with the permit process for dockless?”

Cornish added: “If we do nothing, dockless bikes are going to eventually show up on our streets like the Bird scooters did. The benefit to not rolling out another dock-based system is that we could use those dollars to improve our bike infrastructure instead.”

Weeks remarked that dockless systems work well for outlying areas that wouldn’t be covered by a dock-based system, “but not as well for having bikes in reliable locations that are regularly rebalanced.” Stations, Cornish said, are usually placed near bike lanes, transit stations and low-stress roads, whereas dockless bikes are more spread out.

Officials and advocates have also preached the need for a more equitable system. Both Baltimore Bike Share and the recently rolled out Bird scooters require users to be 18 years old, which leaves out teens and children.

“As a city, we have struggled to provide equitable transportation for all citizens,” Cornish said. “If we can’t do it, we should not put it on private companies to do it for us.”

Dockless providers, such as Ofo and Jump, also set a minimum user age of 18, and require a phone and credit card for locating and renting bikes. For perspective, more than a quarter of Baltimore City residents do not have a bank account, The Sun reported last year.

And while some providers have cash-based options, dockless systems require a phone to hunt for bikes or scooters. Dock-based systems like Baltimore’s allow a user to use cash and a key fob to check out a bike.

“Everything should go through the lens of equality,” said Cornish.

Dorsey supports both options.

“I don’t really concern myself with whether or not docked and dockless bike share could or should work together. I think that we get both and anything else we can, and we just see how things go.”

What’s Next?

If the city moves on from the current system, it must also develop a plan for a replacement.

One challenge has been that Baltimore Bike Share has been unable to secure a system sponsor. Other highly successful programs have relied on a stable sponsor. Portland received $10 million from Nike; Chicago got $12.5 million from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois; Philadelphia was given $8.5 million from Independence Blue Cross.

Mike Heslin, Baltimore market manager for Lyft, has touted the company’s desire to partner with the city. Despite the recent reboot of the system after last summer’s shutdown, Lyft entered into a 3-year, $270,000 sponsorship in February. The deal gave Lyft five company-branded bike share stations in exchange for funding of bike share station infrastructure and maintenance.

Heslin noted Lyft was aware of the problems that led to the shutdown last summer, but was not worried.

“We came into this with open eyes,” he said. “Lyft wants to partner with the system as it grows and gets healthier.”

Notably, the company is also purchasing Motivate, which operates Citi Bike in New York and Capital Bikeshare in D.C., for $250 million, because Heslin said they are interested in complementing city transportation systems, not competing with them.

Despite the issues with the equipment, Baltimore has shown healthy demand for bike share. Between March 2018 and this month, users have logged more than 24,000 trips, which is impressive given that so many stations have been left empty.

“Data shows a strong demand for bike-share in Baltimore and membership is growing,” German, of DOT, said in an earlier email July 11.

But based on data from other cities, it’s likely that Baltimore’s current system is only scratching the surface of its potential. According to the National Association of City Transportation Officials’ 2017 report on bike sharing, Detroit saw 112,000 trips in the first six months of its system in 2017.

Baltimore has only seen 93,000 trips in the first 21 months.

For Dorsey, a reliable bike share program would be key to creating a more complete transportation system to increase Baltimoreans’ quality of life.

“Diverse, robust and accessible transportation and recreation opportunities are necessary to improve the economy, health, safety and resiliency our residents and communities deserve,” he said, “and a bike share system that reaches all of Baltimore can be a great part of making that a reality.”

Meanwhile this week in Chicago and everywhere else. https://www.nbcchicago.com/news/local/divvy-bike-theft-video-489057391.html

Really well researched – Way to Go Brian & Fishbowl !